Convergence: Where West meets East

|

文章导读: |

For around 200 years, two very different systems of medicine have been used in Asia to cure diseases and keep people healthy. The local Asian one is based on traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) — herbal mixtures developed though observation and experience accumulated over thousands of years, but with unknown mechanisms of action. On the other hand, modern medicine, imported from the West, consists of chemically purified compounds that have been discovered through scientific investigation and tested in controlled clinical trials. They differ in the composition of their medicines, the process of diagnosis, methods of proving a treatment's effectiveness, and even in their concept of 'health' (see 'Made in China', page S82).

GRACIA LAM

Are these differences irreconcilable? Or, if TCM is modernized to the point where it can make scientifically valid claims, might it offer new perspectives that can benefit modern medicine — including clues on how to tackle the least tractable diseases and conditions? And likewise, can new perspectives being advanced in the West, such as systems biology, help lay a scientific foundation for TCM?

Spirituality in medicine

Although modern medicine has its roots in herbalism and in ancient Greek traditions that share many similarities with TCM, the practice of medicine was transformed by the Enlightenment and the consequent revolution in science and technology. Since the late eighteenth century, Western-style medicine has incorporated knowledge of anatomy, physiology, chemistry and biology, and its methods are evidence-based. TCM, although it is starting to take on these attributes, still relies heavily on ancient records and traditional practices.

TCM includes many tenets derived from Taoism, Confucianism and ancient Indian philosophies that describe the natural world, life and the human body. Concepts include yin and yang, which represent opposing yet complementary essences of nature; wuxing, which covers the five basic elements of the universe (wood, fire, earth, metal and water); qi or energy; and xue, the blood. This terminology purports to be concerned with disease and human health, but cannot be defined in terms of biochemical or biological facts — or indeed measured. And even the literal translation of these tenets into other languages is misleading.

The modern medical and scientific communities in China and elsewhere are highly critical of such mystical concepts, which are consequently becoming marginalized in China. “The medical practice of TCM is a process of trial and error, and concerns the understanding and control of herbs from the Chinese Materia Medica,” says Daqing Zhang, director of the Center for History of Medicine at Peking University in Beijing. “The philosophical theories were created afterwards to provide the explanatory framework for the practices, and are used to win the patients' trust.”

But thousands of years of history is a long time to cement a belief, and the theories of TCM still have their firm defenders, such as Boli Zhang, president of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CACMS) in Beijing. “We believe in the jing luo [the meridian or energy pathways], but we have not found it yet,” he says. Nevertheless, even in the TCM community, there are fewer Chinese scholars who believe the TCM tenets literally. Indeed, there has been criticism from academics and the media in China, arguing that much of TCM and most of its theories are pseudoscience and that China should bid “farewell to traditional Chinese medicine”1.

Despite these negative sentiments, the Chinese government has started to promote TCM by allocating large funds for research (see 'One step at a time', page S90). Influential figures in the TCM community, such as Boli Zhang and his deputy Baoyan Liu at CACMS, are pushing for the modernization of TCM while also emphasizing its unique qualities. These advocates insist that the traditional TCM practices should be preserved for as long as possible to better investigate their heritage. “The advantages and disadvantages of the two systems are the premise of the integration,” says Liu.

Closing the gaps

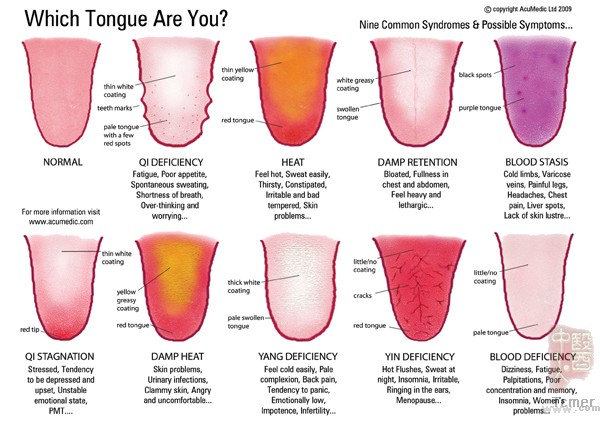

One practice in TCM that is adapting to science is diagnosis. Each patient receives a personal diagnosis based on a TCM syndrome or zheng, which is a characteristic phenotype of identifiable manifestations gleaned from general appearance, listening to and smelling the patient, feeling the pulse and asking questions. TCM diagnosis includes many symptoms considered less important in modern medicine, such as thirst, the tongue's condition, whether the limbs feel cold, and mood. In contrast, modern disease diagnosis is based primarily on clinical signs such as temperature and blood pressure, pathological examination of individual organ functions and biochemical analysis of blood or urine.

“Chinese herbal medicine identifies and treats syndromes rather than diagnosed diseases,” explains Aiping Lu, director of the Institute of Basic Research in Clinical Medicine at CACMS. TCM syndromes are a finer level of classification than disease groupings in modern medicine. Lu's group is collaborating with several Western research institutes on rheumatoid arthritis. In one study, his team used 18 different clinical TCM signs to classify rheumatoid arthritis patients into four subgroups, corresponding to presence of joint symptoms (tenderness, swelling and stiffness), cold pattern (joints and limbs feel cold to the touch, and patient is intolerant of cold), deficiency pattern (including weakness, dizziness, fatigue and nocturia) and hot pattern (including joints that feel hot, vexation, fever and thirst). Then all patients were randomized to receive either modern medicine or a TCM treatment. Each TCM-defined sub-group responded differently to treatment. “The results show TCM syndromes improved the efficacy of both TCM and modern medicine interventions,” says Lu. Notably, patients with cold-pattern symptoms responded better to modern medicine, whereas those classified with a deficiency pattern benefited most from a TCM intervention2. The next step is to analyse the patients' metabolites to look for underlying biochemical differences between the different TCM syndromes, to see if there is a link between TCM diagnoses and modern medical definitions (see 'All systems go', page S87).

The composition of TCM medications is at odds with modern medicine too. TCM uses compound formulae (fufang) that contain several herbs thought to act in unison to restore what TCM practitioners call the patient's 'balance'. “It is an advantage of TCM that multiple drug components can strengthen the therapeutic efficacy and attenuate the toxicity of major component(s) through drug–drug interaction in vivo,” says Wei Jia, co-director of the Center for Research Excellence in Bioactive Food Components at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Another advantage of a formula that acts on several fronts is that each ingredient does not have to be so potent. “If we use medium-active ingredients, which comprise the majority of compounds in nature, we have more potential drug candidates, achieve weaker side effects and have lower R&D costs,” says Zhimin Wang, a chemist at CACMS' Institute of Chinese Materia Medica.

TCM practitioners formulate their herbal remedies according to a set of principles (peiwu), which organize ingredients in any fufang into four functional roles: sovereign, minister, assistant and envoy. The sovereign is the ingredient with major pharmacological activity. The ministers provide additive or synergistic activities. Assistants can either augment the pharmacological effect, detoxify or even counteract an excessively strong action. Envoys harmonize the whole recipe to ensure that all the substances in the fufang are compatible.

There is early evidence supporting the peiwu principles. A team led by molecular biologists Zhu Chen and Saijuan Chen at Jiao Tong University in Shanghai analysed the Realgar–Indigo naturalis formula — a TCM-based leukaemia treatment containing realgar, indigo minerals and the herb red sage root (danshen). They found that the arsenic in realgar could be described as the 'sovereign' as it attacked the main oncoprotein in leukaemia cells; indirubin, the active ingredient in indigo, worked as the 'assistant' to slow leukaemia cell growth; and tanshinone, from red sage root, served as 'minister' to help restore the damaged pathways that prevent leukaemia spreading. Indurbin and tanshinone also worked as 'envoys' to enhance cellular uptake of arsenic3.

“A TCM formula is structural, and using the ingredients should be like a military operation,” says Zhong Wang, a professor at CACMS' Institute of Basic Research in Clinical Medicine, who has developed a concept that covers the science of TCM formulae — fangjiomics4. Fangjiomics separates biological networks into discrete, interactive modules that can be targeted separately but whose biological effect must be considered together. Zhong Wang argues that, compared with the Western model of single-target interventions, TCM combinations are systematic and well ordered.

The long way ahead

“Could Western treatments of chronic diseases be improved by insights from TCM?”

The triumphs of modern medicine in the past 200 years have been most striking in preventing and curing infections and acute disease, and in pain relief. By contrast, progress in understanding and treatment of chronic and degenerative diseases has been slow. And it is these conditions, such as diabetes and Alzheimer's disease, that are responsible for a large portion of the West's soaring and unsustainable healthcare costs. Could Western treatments of these diseases, where there is no infectious agent but rather an internal imbalance in the immune system or other biological housekeeping systems, be improved by insights from TCM?

In modern medicine, chronic conditions are generally treated with prolonged administration of chemical drugs, which can give rise to long-term toxicity or even resistance. That's what happens, for example, with many patients taking isosorbide dinitrate for chronic angina pectoris. The danshen dripping pill provides a better long-term curative effect, claims Jia. As it contains a mixture of ingredients, each individual component can be added at a lower, less-potent dose without compromising the effectiveness of the overall preparation. Moreover, TCM preparations tend to be cheaper than modern pharmaceuticals, he adds.

In addition to being a source of national and cultural pride, Chinese herbal medicines are the most promising source of new drugs for the Chinese pharmaceutical industry, which has always lived in the shadow of Western pharmaceutical giants. China is stepping up its efforts in both academia and the pharmaceutical industry to find safe and effective compound formulae that are acceptable to Western regulatory agencies. Most attempts have focused on isolating a single active ingredient from the TCM preparations. This reductionist, Western approach has led to only a few successes — including the antimalarial drug artemisinin and the leukaemia treatment arsenic trioxide.

So far, no drugs based on established TCM formulae have been approved in the United States or Europe. The nearest example is sinecatechins (marketed as Veregen by German biotech MediGene based in Martinsried), a cream made from a mixture of green tea extracts for the treatment of genital and perianal warts. Sinecatechins was approved in 2006 by the US Food and Drug Administration, and is the FDA's first and only 'botanical' drug — approved on clinical results despite the fact that the active ingredients and the mechanism of action are not known (see 'Herbal medicine rule book', page S98). However, the danshen dripping pill, manufactured by the Tainjin-based Tasly Group in China, has successfully completed phase II trials in the United States and could be the first botanical drug derived from the TCM repertoire.

ACUMEDIC LTD (2009)

“Pharmaceutical regulations in the West are developed according to the Western way of drug R&D, and they are not fit for evaluating TCM drugs,” says Henry Sun, vice-president of Tasly Group. “Of course, TCM should be proved on the basis of scientific evidence.” However, Sun argues that the science is skewed towards testing single agents targeted to single mechanisms (see 'The clinical trial barriers', page S93). “Besides the science, the other major challenge is convincing different groups in the West, from ordinary people to policymakers, to change their prejudices against TCM.”

Top down or bottom up?

The advent of –omics technologies that rapidly measure the entirety of the human complement of, for example, genes (genomics) or metabolites (metabonomics) — and to integrate these diverse data into a complete picture — has given rise to a new way of looking at medicine in the form of systems biology. For many TCM researchers, such as Aiping Lu and Zhong Wang, systems biology is potentially a way to understand TCM using Western scientific methodology.

“The major challenge of the integration of TCM and modern medicine is the translation from TCM experience and concepts into biochemical and biological meanings that Western scientists can understand,” says Jan van der Greef, a systems biologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands. “Systems biology is an ideal theory and analysis tool that can bridge the two systems.”

Leroy Hood, president of the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle, Washington, and regarded by many as the field's founding father, has introduced what he calls '4P healthcare': predictive, personalized, preventive and participatory. This concept, Hood contends, is the new paradigm of modern medicine in a systems biology era. 4P medicine focuses on the biochemical networks underlying health and disease, then aims to treat and prevent disease by identifying and countering perturbations in the biological networks — a concept highly reminiscent of the TCM philosophy. Thanks to systems biology, the gap between the two medical systems is starting to narrow. For example, recent advances in medical technology are allowing the application of new phenotyping technologies that can simultaneously characterize the multiple drug responses to dietary preparations, such as pu-erh tea. In a proof-of-concept study in humans, a team led by Jia quantitatively measured the absorption of pu-erh tea molecules, the output of gut bacteria metabolism, and the human metabolic response profile in the urine5. “The phenotyping strategy can further differentiate disease subtypes that are correlated to different TCM syndromes,” says Jia. This, in turn, will “improve doctors' ability to personalize treatment and to predict an individual's response to a drug regimen”.

But Jia and others are aware that the technology and methodology of systems biology are still immature. “We have to first develop network models to simulate a pathogenesis: for example, the transformation of normal cells to cancer cells,” says Jia. “The second step will be to model a multi-component agent targeting the multiple sites involved in the transformation process.”

East meets West

The absence of scientific development processes and controlled clinical trials has held back the integration of traditional Asian medicine and modern medicine for centuries. Some of its concepts appear more magical than practical, and, without a physical basis, have resisted measurement and observation. But slowly these differences are resolving.

Much of the drive for integration will come from China and its neighbours. “We should build our own methodology to evaluate the unique features and efficacy of TCM,” says Zhimin Wang. “There are so many possible ways of integration between TCM and modern medicine. We should keep our minds open.”

The days of competition between these two systems could well be gone. “The two systems cannot replace each other,” says Boli Zhang. “But instead they will fill each other out.”

Convergence: Where West meets East

Peng Tian

Nature Volume: 480, Pages: S84–S86 Date published: (22 December 2011)

doi:10.1038/480S84a

Published online 21 December 2011

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v480/n7378_supp/full/480S84a.html

200年以来,两个非常不同的医学系统一直在亚洲运作着,治疗疾病,保证人民的健康。亚洲本土的医疗基于中医理论和中药方剂——通过几千年的观察和经验积累发展而来的草本药物的混合物,但不知道作用机理。而另一个则是现代医学,从西方进口的,由经科学研究发现并通过控制的临床试验测试过的化学提纯化合物组成。它们在药物组成,诊断过程,证明治疗手段有效的方法,甚至在健康的看法上都有着差异。

这些差异是不可调和的吗?或者说,如果中医能够在一些关键上做出有科学依据的论断,也许能够提出新的有益于现代医学的观点——包括怎样去处理最棘手的疾病和情况的一些提示?同样地,西方提出的一些新观点,例如系统生物学,是否能够帮助中医建立一个科学的基础?

医学的精神

虽然现代医学扎根在本草医学上,而且古希腊传统医学和中国传统医学有着许多相似之处,但是其医学的实践方法还是因启蒙运动和随后的科技革新而发生了改变。自十八世纪以来,西方模式的医学由解剖学、生理学、化学和生物学的知识构建而成,而它的方法是根于证据的。中医,虽然开始接触这些东西,但仍然是非常依赖于古代的文献记录和传统的实践操作。

中医包含许多源自道家、儒家和古印度哲学的描述自然世界、生命和人体的原理。比如阴Yin和阳Yang的概念,代表着自然对立互补的本质;五行Wuxing,涵盖了宇宙的五种基本要素(木,火,土,金和水);气Qi,或者说能量;还有血xue,即血液。这些术语是就人体健康和疾病而言的,但是不能用生物化学或生物学上的客观事实来定义,或者实际上是无法测量的。甚至把这些原理直译成其它语言就会引起误解。

在中国和其他地方的现代医学和科学界对于这些神秘的观念充满了质疑,以至于在中国这些思想遭到排斥和忽视。“中医的医疗实践是一个反复试验的过程,涉及到如何理解和控制使用中草药。”北京大学医学史中心主任张大庆说。“随后创造出一些哲学理论为这些医疗实践提供一个说明的框架,并用来取得病人的信任。”

但是数千年的历史让这些教条有足够长的时间去巩固,而且中医的理论仍然有它坚实的捍卫者,比如张伯礼,中国中医科学院院长。“我们相信经络[人体的子午线或能量的通道]的存在,但是我们还没有找到它。”他说。虽然如此,即使在中医界,相信中医理论的中国学者越来越少。实际上,在中国,学术界和媒体都对中医发出过批判,认为中医的许多地方和它的绝大部分理论都是伪科学,中国应该表示和中医说再见。

尽管有很多负面的看法,中国政府仍通过分配巨大的研究资金来支持中医。中医界有影响力的人,例如中国中医科学院的张伯礼和副院长刘保延,在推动中医现代化的过程中同时强调其独特性。这些拥护者坚持认为应尽可能地保护中医传统医疗实践的延续,从而更好地继承这些遗产。“明晰两个医疗系统的优点和缺点是它们整合的前提。”刘保延说。

填补缝隙

使中医适应科学的一步是在诊断上。每一个病人都是依据中医上的“症”来得到个人的诊断的。“症”是一些通过望闻问切得来的可识别的典型的临床症状。中医上的许多症状在现代医学看来不是很重要,比如口渴,舌头的情况,四肢是否发冷和病人的情绪。而现代的疾病诊断则主要根据临床的症状诸如体温、血压、单个器官功能的病理学检查以及血液和尿液的生化分析。

“中草药更多时候是对症而不是对病。”吕爱平解释,他是中国中医科学院中医临床医学基础研究所常务副所长。中医的症候相比现代医学的疾病分类法而言,是一种更好的分类方式。吕的团队正和几个西方研究所展开风湿性关节炎方面的合作。在一项研究中,他的团队根据18个不同的中医症候把风湿性关节炎病人划分成四个亚组,分别是关节症状组(压痛、肿胀和僵硬),寒组(关节和四肢摸上去发冷,并且病人难以忍受寒冷),虚组(包括乏力,头晕,疲劳和遗尿)和热组(包括关节发热、烦躁、发烧和口渴)。然后所有的病人都随机获得现代医学或者中医的治疗。每一个经中医定义的亚组使用相对应的治疗方法。“结果显示中医症候同时促进了现代医学和中医的疗效。”吕说。特别是归为寒组的病人对现代医学的治疗反应更好,而那些被归为虚组的病人对中医的治疗反应最佳。下一步是要分析病人的代谢物来获得不同的中医症候之间潜在的生化差异,从而明确中医的诊断和现代医学的术语之间是否有着联系。

中医的药物组成也和现代医学不同。中医使用由几种草药构成的复方同时作用于人体去恢复中医师所谓的病人的平衡。“通过药物和药物之间在体内的互作,运用多种药物成分来加强疗效,减少主要成分的毒副作用,这是中医的优点。”美国北卡罗莱纳州大学食物生物活性成分卓越研究中心的联合主任Wei Jia说。

除了上述优点之外,复方的优势还在于不需要每一个成分都是强有效的。“如果我们使用粗提的有效成分,其中包含自然生成的大部分化合物,那么我们将有更多可能起效的药物作用人体,而且副作用更低,研发成本也更少。”中国中医科学院中药学研究所的药剂师Zhimin Wang说。

中医师根据一些配伍原则来组合他们的药方,即每个复方都包含“君臣佐使”四部分。“君”指的是主要起效的药物。“臣”有增效作用。“佐”有增效,解毒或者抵消过分强烈的药效的作用。“使”则是起调和作用,保证复方中的所有药物能够相互兼容。

有一些初步的证据支持配伍原则。上海交通大学分子生物学家陈竺和陈赛娟领导的队伍分析了复方黄黛片的成分——中医用于治疗白血病的药方,包括雄黄、青黛、丹参。他们发现雄黄中的三氧化二砷可以被称为“君”,它攻击白血病细胞主要的肿瘤蛋白;靛玉红,青黛中的有效成分,发挥“使”的作用来减缓白血病细胞的生长;丹参酮,作为“臣”去修复损伤的信号通路来阻止白血病的扩散;靛玉红和丹参酮作为“使”去加强细胞对三氧化二砷的摄入。

前方路漫漫

过去200年间现代医学主要是在阻止和治疗传染病、急性病以及缓解疼痛上取得辉煌的成就。相比而言,在理解和治疗慢性病和退化性疾病上进展缓慢。而正是这些疾病,例如糖尿病和阿尔兹海默症,是引起对西方医疗保健费用的不断上升和难以维持的主要原因。通过对中医的深入了解,是否能够改进西医对这些由免疫系统或其他的生物内稳系统的内部失调,而非感染导致的疾病的治疗呢?

现代医学对于慢性病的治疗通常是采用长期服药的方式,而这容易导致长期的毒性或者耐受性。例如许多长期服用消心痛(硝酸异山梨酯)的心绞痛患者就有上述情况。而丹参滴丸则提供了一个更好的长期治疗效果,Jia说。因为它包含一系列的成分,每一个单独的组成可以少量低效力给药而又不使整个制剂的效力打折扣。此外,中药制剂一般比现代药物的价格便宜。他补充说。

中草药不仅是一种值得国家和文化自豪的资源,而且对于总是在西方制药巨头们的狭缝中生存的中国制药产业而言,也是开发新药的最有前途的资源。中国正逐步加强在学术和制药产业上的努力,来寻找能够被西方管理机构所接受的安全有效的复方。大部分的尝试集中在从中药制剂中分离单一的有效成分。这仍是还原论的体现。这种西方手段仅产生了很少的成功例子——包括抗疟药青蒿素和治疗白血病的三氧化二砷。

直到目前为止,还没有依据中医理论研发的药物得到美国和欧洲的认可。最接近的例子是sinecatechins,一种绿茶提取成分的混合物乳膏,被用于治疗生殖器和肛周疣。Sinecatechins是在2006被美国食品和药物管理局批准通过的,是FDA第一个和唯一一个植物性药物,批准依据是临床的结果,尽管其起效成分和作用机理未知。不过,由中国天津天士力集团制造的丹参滴丸已经顺利通过了美国的二期临床试验并将有望成为第一个被认可的从中国传统医学中研发出来的植物性药物。

“西方的制药监管规程是根据西方开发药物的方式制订的,而它们并不适用于中药的评估。”天士力集团的副总裁Henry Sun说。“当然,中医需要在科学证据的基础上被证明。”但是,Sun认为科学长于检测针对单一机制的单一药物。“除了科学,另一个主要的挑战在于如何说服西方的不同群体,从普通民众到决策者,改变他们对中药的偏见。”

自上而下还是自下而上?

快速测量整个人体组分,例如基因和代谢物,并将这些多样的数据整合到一张图上的组学技术的出现,为用系统生物学的方式看待医学提供了一条新的途径。对许多中医研究员来说,例如吕爱平和Zhong Wang,系统生物学也许可以提供一个用西方科学方法理解中医的路子。“中西医结合的主要难点在于如何把中医的经验和观点转变为西方科学家可以理解的生物化学和生物学上的含义。”荷兰 Leiden University 的系统生物学家Jan van der Greef说。“系统生物学是一个理想的理论和分析工具,能够连接这两个系统。”

Leroy Hood,西雅图系统生物学研究所所长,被许多人认为是这个领域的创建人,介绍了他所谓的“4P医疗保健”,即预测predictive, 个体化personalized, 预防preventive和参与 participatory。Hood倡导的这种理念,是诞生于系统生物学时代的新的现代医学范式。4P医学关注健康和疾病下的生化网络,然后识别并抵制生物网络的扰动。这种理念很容易让人联想到中医的哲学。感谢系统生物学,让两个医学系统间的差距变窄了。例如,最近一些医学技术的发展允许新的表型技术应用在同时观察饮食后的多种反应,比如喝普洱茶后。在一个人们的“观念-验证”研究中(即研究哪些观念是对的),Jia领导的小组定量地测量了普洱茶微粒的摄入量,内脏细菌代谢物的输出量和侧面反应人体代谢的尿液成分。“表型策略还可以区分通过不同的中医症候划分的疾病亚型的差异。”Jia说。而这些将会“提高医生个体化治疗的能力并预测某一个个体对一种给药方案的反应。”

但是包括Jia和其他人在内都意识到系统生物学的方法和技术仍不成熟。“我们首先要发展出发病机制的模拟网络模型(生化代谢网络之类):比如,从正常的细胞转变为癌细胞。”Jia说。“第二步是建立一个靶标为转变过程中多个位点的多组分药物模型。”

东方面对西方

科学的开发流程和控制临床试验的缺失阻碍了几个世纪以来亚洲传统医学和现代医学的整合。它的部分内容如其说像治疗,不如说更像是魔术。同时由于缺乏物理基础,难以被测量和观察(经络之类)。然而,这些差异正缓慢地缩小。

这种整合的实施绝大部分来自中国和她的邻国。“我们应当建立一套我们自己的评估中医特色和功效的方法”,Zhimin Wang说。“中西医结合有许多可能的途径,我们应开阔自己的思维。”

两个医疗系统竞争的日子很有可能会消失。“这两个系统无法相互取代,”张伯礼说,“相反,他们会相互补充。”

|

|

-

没有相关Article